DOMESTIC VIOLENCE: THE COST OF DOING NOTHING

Ground-breaking research at University of Galway on domestic violence as an economic issue, has had a fundamental role in shaping the global research agenda, legislation and policy.

Dr Nata Duvvury, Senior Lecturer and Director, Centre for Global Women's Studies, University of Galway

Dr Nata Duvvury, Senior Lecturer and Director, Centre for Global Women's Studies, University of Galway

SUMMARY

Ground-breaking research at University of Galway on the economic cost of domestic violence (DV) in low and middle-income countries has been pivotal to developing new legislation and policies to protect women in Egypt, South Sudan and Vietnam. Women experience DV behind closed doors; however, its impact reaches beyond the individual and their family, having serious consequences for national economies. Recognition of these consequences is key to governments enacting new legislation, investing in support and judicial services, and scaling up prevention efforts. University of Galway’s theoretical frameworks, toolkits and manuals are increasingly used worldwide to guide costing projects, ultimately seeking to eliminate this pervasive form of violence.

Globally, 1 in 3 women experience domestic violence

COSTING RESEARCH

Globally, 1 in 3 women experience DV. In addition to damaging individual and family health, this violence undermines households’ economic security and living quality, while limiting the effectiveness of programs to improve the well-being and capabilities of communities across low and middle-income countries.

For example, 2011 Vietnam costing research, led by University of Galway, indicated that women spend nearly 30% of their monthly income on healthcare or replacing broken or damaged property following instances of DV. Equally, businesses and the overall economy lose the productivity of women survivors - lost productivity, in days, was equivalent to a 4.5% reduction in the female working population in Ghana in 2019. As countries strive to expand women's economic participation to accelerate economic growth and eradicate poverty, ensuring the well-being of citizens, this loss is substantial.

Photo: UN Women/Pathumporn Thongking

Photo: UN Women/Pathumporn Thongking

Led by Dr Nata Duvvury and Dr Srinivasan Raghavendran, interdisciplinary researchers at the Centre for Global Women's Studies (Dr Stacey Scriver, Dr Caroline Forde and Dr Mrinal Chadha) have built a robust evidence base on DV’s costs in the Global South. Generally, costs of DV in the Global North are based on police, health and other administrative data, with a primary focus on the costs of providing services to survivors. However, in the Global South data is often lacking, or of poor quality, and alternative methods are required, including survivor and service provider surveys. The research has involved several projects across a range of countries, including Egypt, Ghana, Mongolia and Pakistan. Conducted in partnership with leading multilateral agencies (UN WOMEN, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the World Bank and bilateral donors such as AusAid and the UK Department for International Development (DFID), it has developed innovative methods and conceptual frameworks.

Photo: UN Women/Pathumporn Thongking

Photo: UN Women/Pathumporn Thongking

The Egypt economic cost of gender-based violence survey’. Cairo: UNFPA.

The Egypt economic cost of gender-based violence survey’. Cairo: UNFPA.

DETAILS OF THE IMPACT

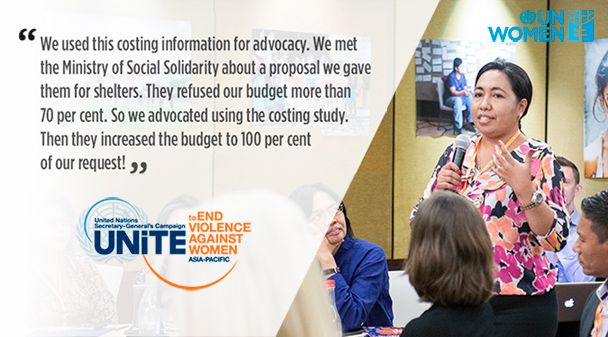

A central objective of DV costing research is the translation of findings into practical recommendations that inform policy, practice and resource allocation. By establishing a robust evidence base, the research has underpinned government actions to increase awareness and enhance the response to DV. This has led to new and strengthened violence against women (VAW) legislation and to more and improved survivor services. Globally, agencies working to eliminate DV are now equipped with the tools and skills, underpinned by the methods and frameworks developed by the University of Galway research team, to produce cost estimates and advocate for a comprehensive and adequately funded government response.

New Legislation

As a result of research projects in Egypt (2015) and South Sudan (2015 -2019) led by Dr Duvvury and her team, both countries have proposed new legislation to combat DV. For example, South Sudan’s Minister for Gender and Child Welfare announced the government’s commitment to pass a new law at the launch of the cost research report in April, 2019. The first of its kind, the draft Anti-GBV Bill is currently awaiting review by the South Sudanese Parliament1 (Autumn 2020). The draft bill cites the research study as one of the law’s foundational documents.

Enhancing Services for Survivors of DV

The research has prompted governments in four countries to review and enhance existing service provision or to develop new services to support and protect DV survivors.

Ghana: the study findings on the economic loss due to violence was used by women’s organisations to press the President of Ghana to commit a dedicated budget to survivor support services.2

Egypt: To improve the criminal justice response to DV, in 2018, the Egyptian Ministry of Interior increased the number of female police officers and integrated a lecture for combating DV into the police academy curriculum to ensure a more effective response by those on the frontline. There is now a special unit of women police officers for combatting VAW and, in 2019, 140 police officers received specialised training from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime.3

Widening acceptance and uptake of DV costing

The research team’s success in mainstreaming the concept that DV is an economic as much as a social concern - and therefore justifies Government attention - is evident in the integration of the DV costings in national and regional economic strategies and the ongoing demand for new costing projects.

Following Duvvury’s 2018 publication of the first Arab guide on how to cost VAW, the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ECSWA) concluded the need for costing studies in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Tunisia and Saudi Arabia.

One of the most important developments is the UN’s decision to develop a Global Costing Tool. Inspired by research in South East Asia to estimate resource requirements to support and implement anti-DV policies, the tool gives Governments, UN agencies and other organisations addressing VAW access to manuals and resources to use in the implementation of the ESP. The costing tool was launched in September 2020.

“Dr. Duvvury and her team’s research … has helped shape thinking at a global level, and specifically the development of a methodology to estimate the resource requirements for a minimum package of services for selected interventions in the UN Joint Global Programme on Essential Services, which UN Women co-leads. The Centre for Global Women’s Studies completed a Global Costing Tool…[which] is helping to inform national planning, programming and budgeting processes in the countries in which UN Women, and its partners work and is helping Governments and civil society to better understand what is required for service provision and why this is necessary.”

Transforming Attitudes

Dr Duvvury and her team’s research has positively affected the lives of individual women, while also sensitising the thinking of state and international actors to better understand and measure the impact of violence. The new costing projects commissioned and funded by Governments and international agencies around the world are evidence of how the research has helped to change attitudes. Having a reliable method to assess the wider economic cost of DV gives policy makers an evidence-based justification to take action, influencing transformative impacts for decades to come.

Pathways to Impact

Achieving impacts from this research has involved Dr Duvvury and her team tirelessly pursuing a variety of dissemination channels over many years including reports, peer-reviewed academic journal articles, policy briefs, flyers, infographics, brochures and social media campaigns, news stories and opinion pieces, and online and face-to-face launch events/workshops.

Developing a close collaborative relationship with partners in the third sector and UN organisations has also been essential. Their ability to secure interest in, and funding for, costing studies among stakeholders has been crucial in maintaining momentum. In addition, such partnerships have resulted in the smooth and successful production, dissemination and implementation of research findings.

Academic Impact

Not too long ago, estimating the costs of VAW was viewed as ‘inhumane’ and ‘unethical’, as it was perceived as placing a financial value on pain and suffering. Such a view however meant that aspects of the impact of VAW were being overlooked and knowledge was limited. Dr Duvvury and team’s work has changed this narrative, contributing to a better understanding of the value of such work in both complementing and strengthening the human rights and public health arguments for a comprehensive response to VAW. This has, in turn, led to a paradigmatic shift in the research agenda, which now provides a platform for costing studies.

Ghana: The study findings on the economic loss due to violence was used by women’s organisations to press the President of Ghana to commit a dedicated budget to survivor support services.2

Egypt: To improve the criminal justice response to DV, in 2018, the Egyptian Ministry of Interior increased the number of female police officers and integrated a lecture for combating DV into the police academy curriculum to ensure a more effective response by those on the frontline. There is now a special unit of women police officers for combatting VAW and, in 2019, 140 police officers received specialised training from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime.3

THIS RESEARCH IS HELPING TO GIVE VISIBILITY TO AN OFTEN INVISIBLE PROBLEM

Funding

References to the Research

Ashe, S., Duvvury, N., Raghavendra, S., Scriver, S. and O’Donovan, D. 2016. ‘Methodological approaches for estimating the economic costs of violence against women and girls’. London: UK Aid.

Duvvury, N., Minh, N. and Carney, P. 2012. ‘Estimating the cost of domestic violence against women in Viet Nam’. Hanoi, Viet Nam: UN Women.

Duvvury. N., Attia, S., El Adly, N. et al. 2015. ‘The Egypt economic cost of gender-based violence survey’. Cairo: UNFPA.

Duvvury, N., Scriver, S., Vyas, S. and Ashe, S. 2016. ‘Estimating resource requirements for responding to violence against women in South East Asia: Synthesis of findings and lessons’. New York: UN Women.

Duvvury. N., El Awady, M., Benkirane, M. (2017). Estimating costs of marital violence in the Arab region operational model. Beirut: UN.

Duvvury, N and Forde, C (2020) Guidance on Estimating Resource Requirements for a Minimum Package of Services. Galway:

University of Galway.

Elmusharaf, K., Scriver, S., Chadha, M., Ballantine, C., Sabir, M., Raghavendra, S., Duvvury, N., Kennedy, J., Grant-Vest, S. and Edopu, P. 2019. Economic and Social Costs of Violence Against Women and Girls in South Sudan: Country Technical Report Galway: University of Galway.

Raghavendra, S., Duvvury, N. and Ashe, S. 2017. ‘The macroeconomic loss due to violence against women: The case of Vietnam’.

Evidence Sources

1 Call for action to end gender-based violence and impunity for GBV perpetrators in South Sudan

2 Final Performance Evaluation Report of What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls Programme, UK Department for International Development.

3 Improving the Criminal Justice Response to Violence against Women in Egypt

The photos in this case study do not represent women and girls who themselves have been affected by

gender-based violence nor who accessed services.